Renoir: Between Bohemia and Bourgeoisie: The Early Years

Category: Books,Arts & Photography,Individual Artists

Renoir: Between Bohemia and Bourgeoisie: The Early Years Details

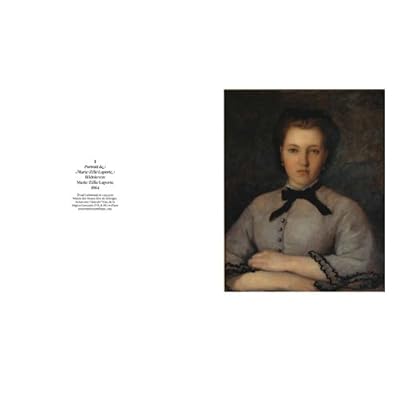

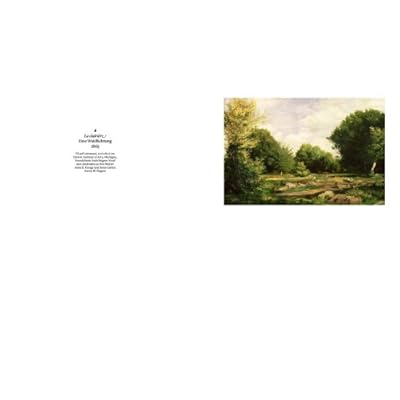

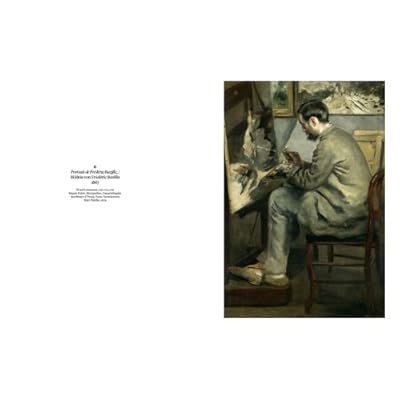

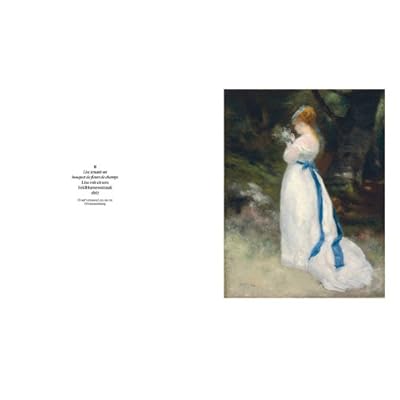

Review Gone is the innocent secessionist dream of the "painters of modern life," the programmatic heroism of the refusés who rejected the recognition that came with exhibiting work in the Salon. Nor is our image or Renoir any longer the rosy one of artistic legend. His biography has become more contradictory, undermined by episodes long left unmentioned the Kunstmuseum Basel [exhibition] shows Renoir's work before his "Arcadian turn," that is, from the years before his social and commercial success At the Basel show one wanders back and forth between the works of an ambitious and talented young painter still getting his footing in the vibrant Paris art scene between 1864 and 1879. He looks back to Narcisse Diaz, is impressed by Courbet, and has before his mind's eye the works of his friend Manet, the true initiator of Impressionism After immersing itself in mythology, the painting of modern life seeks a new location for woman But what in Manet is the result of deep reflection on art history, in Renoir springs from a desire for naïve sensuality In a poetic passage in In Search of Lost Time, Proust wrote, "Women pass in the street, different from those we used to see, because they are Renoirs." (Willibald Sauerländer The New York Review of Books 2012-08-16) Read more

Reviews

The last two years have seen an unusually large number of Renoir exhibitions, and their attendant catalogues, which have focussed mostly on the middle and, even more so, the late works. The blockbuster of them all was the huge 2010 "Renoir in the Twentieth Century, " in Paris, Los Angeles, and Philadelphia, with its 440-page catalogue. Also in 2010, The Clark Art Institute mounted "The Genius of Renoir: Paintings from The Clark" in Williamstown and Madrid, presenting paintings mostly from the 1870's and 1880's, reflecting its own collection, the earliest Renoir in which is from 1874. Then came the 2012 opening of the Barnes Foundation's new museum, also in Philadelphia, and to celebrate they published the monumental catalogue raisonne of their 181 Renoir paintings, 85% of which were also created after 1900, the year when Renoir turned 59. And also this year was the Frick Collection's "Renoir: Impressionism and Full-Length Painting," centered around their "La Promenade" from 1875-76 and featuring work mostly from the late 1870's and the following decade. (See the various reviews of those catalogues on this website.)In the face of all that concentrated attention, one could almost forget that there was also an early Renoir. And so it was good that this summer's exhibition at the Kunstmuseum Basel was "Renoir Between Bohemia and Bourgeoisie: The Early Years," and that Hatje Canz has published this very fine English version of the original German catalogue (even though the exhibition didn't leave Basel). There are fifty excellently printed full-page reproductions of paintings from 1864 to 1880, many of which are not frequently encountered in other Renoir books. These are accompanied by eighty-seven companion illustrations, including some rarely seen examples of Renoir's painting on porcelain, and a number of period photographs of the painter, his friends, and their surroundings. Each painting is seconded by a brief but well annotated and informative commentary. There are six scholarly essays, two of which focus on Renoir's early experiences of other art, especially the 17th- and 18th-century pictures in the Louvre, in which he spent hours looking and copying. The other four essays are more biographical in orientation, aimed especially at deconstructing the many myths that early commentators, abetted heartily by Renoir himself, had woven around his younger years. Michael F. Zimmermann, for example, vigorously debunks the picture that Ambroise Vollard had created in his volume of "Intimate Recollections," frankly calling it "fiction" (24). There is less here of the informational apparatus that such catalogues frequently provide; each painting is identified by name, size, and current location, but there is no record of provenance, prior exhibitions, or specialized literature. There is a good chronology of the painter's life until 1880, but only the slightest of selected bibliographies, and no index. Given its limited focus, this is probably not a volume to be recommended to a broad readership or to some one with only a general interest in Renoir and Impressionism. But a reader with a particular focus on Renoir or who simply wishes to see more of those early paintings in good reproductions, or to have a few essays about the years that Renoir in later life was reluctant to recall, will find much of interest in this handsomely produced catalogue.